| ||||||||

|

|

Just

a Fall PAGE

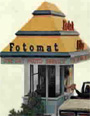

TWO He moved the gun an inch closer, to the lid of the little window. And even though his left eye was saying, "Oh, I don't know, what would you recommend?" his right eye was shouting at me, "ALL the film, you stupid bitch." To add insult to the incident, every person I recounted the robbery to laughed when I confessed the guy never got out of the car, or even rolled his window down all the way. Even the cops said, "Now wait. You gave him all the money and all the inventory in the store and the guy never got out of his car?" Here's why. There's no place to run and hide inside a Fotomat booth. I mean, there's a wall two feet in any direction and he was on the side with the door. I could have ducked in a corner, but my mind calculated that no matter where he fired the gun into the booth, the bullet would ricochet and hit me. And, though I wasn't really doing anything with my life, I wasn't ready to fold my hand, either. A week

later, another memorable thing happened. A two-year-old girl bounced

off the side of my Foto booth. I had just arrived for the evening

shift, overly alert, no longer feeling safe in my controlled, Petri

dish environment. A 1982 Oldsmobile caught my eye as it made a tire-squealing

turn out of the 7-Eleven parking lot and into traffic. The back

door of the car flew open and a bundle was propelled out across

the asphalt. Only after it somersaulted against the door of my booth

and rolled back onto the drive-thru did I realize it was a small

child, a little brown-eyed girl who looked up at me through my sliding

glass window. Without a thought, I threw open the door of the booth

and grabbed the child up off the pavement. It was only after she saw her mother's terrified face and heard the shouts of people saying, "How horrible," "She could have been killed," and "She must be hurt," did she start to cry. Until then, the incident had just been a temporary change in placement. Not pleasant, perhaps even painful. But in her innocence she was willing to accept it for exactly what it was: a fall. I certainly know much worse things could have happened to that little girl. They didn't though, and her resilient little body carried her to my door and I got to look into her fearless eyes. I could

have died at gunpoint for misinterpreting a look. You know, choosing

the wrong eye. I didn't though. I was only reminded of the pointlessness

of being afraid of life. Because if you're alive, and you can think

and feel and make decisions, then it's never a waste. And, if you're

dead, then you are. Anything short of that is a fall. Just a fall.

|

As

I was emptying the drawer into a plastic bag, he hissed, "Throw

that good film in, too," motioning with his gun to the boxed

film display next to the register. Due to the lack of focus in his

dead eye, I wasn't sure which film he thought was the good stuff,

so I asked, "Is your camera 35 millimeter or a Polaroid?"

As if he would tell me. As if I could use it later in the police

report. "Yeah, good looking guy, dead eye, probably has a Fun

Flash Instamatic camera."

As

I was emptying the drawer into a plastic bag, he hissed, "Throw

that good film in, too," motioning with his gun to the boxed

film display next to the register. Due to the lack of focus in his

dead eye, I wasn't sure which film he thought was the good stuff,

so I asked, "Is your camera 35 millimeter or a Polaroid?"

As if he would tell me. As if I could use it later in the police

report. "Yeah, good looking guy, dead eye, probably has a Fun

Flash Instamatic camera."